Back

This is an excerpt from Mischa's personal blog. Read the full post here.

Why Was UBC Solar So Awesome?

During the first general meeting of each new term, one of the first things the Captain would tell new recruits is that on a design team, you get out what you put in. I’d actually like to go a step further than this - when you put 100% of your effort and focus in, you will get 110% back out. As an engineer and teacher, I always marvel at complex systems where the net behavior consists of more than the individual sum of its parts. UBC Solar was that complex, positive-feedback system, where the more energy you put in, the more energy would be created. As I developed a sense of ownership over the team’s generational success, I found that the more focus and energy I put in to elevating the team, the more focus and energy I received in return.

When reflecting on Why Do I Want to Do, I noted that strong communities allow their members to take energy from them, and later rely on those same members to return that energy to make the community stronger.

This return of energy from the team’s spirit manifested itself in two major ways that propelled me to be more focused, work longer nights, and literally dream about my design team.

The Only Controllable Variable Is Your Effort

Energy is Infectious

Working with Serhii as co-ops at Sanctuary AI, a startup in the thick of a hundred-million-dollar series B round of fundraising, I understood that our mindsets around leading UBC Solar were very similar to those of running a startup. The key characteristic of running a startup that I resonated with was that the only controllable variable to achieving success was my effort (props to Cansbridge for this phrase). If I wanted to spend hours thinking of ways to make the team work harder, smarter, and faster (Weight, Watts, Time), then we would, and if I didn’t take that time, we wouldn’t.

Fight Entropy with Energy

During my January 2024 reflection a year after becoming Electrical Lead, I noted that I was a “boss at project management” and that I should continue to “fight the entropy and sweat to make your procedures better (because they always can be)!“.

Something that makes me proud is that I try to match and magnify the energy of others in all my interactions. The act of doing this is selfish - attempting to generate energy makes me feel more active, awake, and positive. Fortunately, it’s a selfish act that positively influences others too! Never will I be louder, more silly, more memorable, or motivational than when I’m trying to increase someone else’s energy.

Whether it was early in the morning or late at night, I felt it was important for people to see that their leader was the most excited out of the bunch to be working on Solar, and that this energy was consistently strong to take us to competition. The energy I exuded was infectious - I remember being offline for four days when I was in Ottawa, and coming back to fairly quiet slack channels. The day I returned, I sent out around 10 messages to members and leads, and when I woke up the next day, the number of unread DMs and conversations that my previous messages sparked had spread across the electrical team.

Creating energy is as simple as the act of instantly responding to a member’s message in Slack, putting the ball in their court and encouraging them to move faster.

Critically, I wanted the energy I exuded to be strong and consistent. This was something I admired in Serhii as team Captain, and a quality I strived to match - I wanted to be a lead that all members were proud to have representing their team. This idea of being a strong source of energy that other members could emulate fed into the aspects of my leadership style dedicated to “running UBC Solar like a startup”, and as part of the leadership team of a self-described startup, I felt personally responsible for being a professional presence on the team.

The Importance of Professionalism

Professionalism at UBC Solar was important to me for two reasons. One was that the more gravity I exhibited and vocalized towards my actions on the team, the more seriously I hoped others would take their responsibilities on the team.

The second is because the more seriously I took my experience at Solar, the easier it was for me to get into the flow state of working on team-related items. Feeling like it’s your professional duty to be energetic, composed, and prepared makes it easy to readjust the priorities in your life. As I focused more on UBC Solar, the professionalism and responsibility I felt towards the team became magnified, causing me to produce more and more energy as a leader. Pushing past my previous limits of energy and time spent on the team, I felt stronger and more capable of putting in even more work - a positive feedback loop that would allow me to get five hours of sleep for one or two weeks straight and still wake up focused and ready to work each day.

I didn’t initially make the connection to professionalism as a tool for focusing energy - I’d just always felt that professionalism in activities where you’re dealing with people outside of your close friends is important. In high school, as part of the John Oliver Digital Immersion Mini School, our class regularly went on week-long trips around BC, during which the teachers heading the program impressed upon us the fact that we were representatives of the mini school, and that our actions directly impacted the public perception and success of future trips.

As well, as a lifeguard for the City of Vancouver, I worked at Hillcrest, the city’s largest aquatic center. To be an effective lifeguard, one must be professional above all else - this is what makes people listen to you as you try to prevent accidents before they occur and take control of life threatening situations if they arise. As a lifeguard, when taking your lunch break, you always turn your shirt inside out so that members of the public don’t perceive you as “on duty”. I wore my Solar merch like it was my lifeguarding shirt - when it was on, I was on.

Hillcrest aquatic center, where some of the most professional lifeguards in the city work

Excitement About New Ideas

Another personal quality that synergizes with creating energy in my surroundings is that I am a relentless optimist. On an engineering design team, where technical and interpersonal challenges come up every single day, this quality allowed me to stay positive and resilient in the face of adversity. A shipment was delayed by two weeks - where can we get it locally? That trace on the PCB was too small - let’s add an external wire in parallel. When a problem would come up on the team, my mind would snap to potential solutions and skip the regular “stages of grief” which can paralyze other managers.

While being a relentless optimist was useful when reacting to situations, it was even more useful to proactively identify and seek out solutions to problems before they could occur. On a student design team operating as a startup building a solar powered race car, the only limit to the optimizations you can make to the team is your imagination and curiosity. Fortunately, I was surrounded by a lot of big thinkers who inspired me to think proactively.

Andrew, the previous BMS lead, was great at ideating new ways of working for the team. He singly-handedly created a Google-Forms-to-Github-Issues pipeline that greatly streamline our recruitment process, allowing us to quickly sort through over 130 applicants per cycle. Also, remember the team wiki I keep referring to? Andrew set that entire framework up.

Nic, the previous Electrical Lead, was also excellent at proposing new ideas. After he returned from his co-op at Tesla and before graduating to work there full time, Nic would drop by the bay to check on our progress, and while we chatted, would challenge me to consider high-concept new ideas. In everything from automated Github workflows to Altium library lifecycles, Nic presented ideas around implementing the custom tooling made by fast-moving industry giants at levels which could be leveraged effectively by the team in the near future.

Some of my fondest memories from January-April 2024 were heading over to UBC’s Browns with Nic and Joe (Formula E’s previous Electrical Lead and present Captain), and listening to them talk about running teams, ideas from industry, and new technical design frameworks they found exciting. Joe is an engineer’s engineer - if there’s a way to optimize weight, watts, and time, he’s either heard about it, or has already implemented it. The inspiration he’s sparked from our conversations about how Formula E executes their project management and technical designs is something I am so thankful for, as it has genuinely opened my mind to what’s possible on a student design team.

As I was exposed to more ideas for potential team frameworks, my mind began filling with ideas when I wasn’t working on Solar. I’d be biking to a friend’s house and suddenly pull over to the side of the road to write down an idea for helping members lead up, or make our PCB designs less prone to error, or I might be walking by an computer supply store and think “I wonder if they’ll sponsor our team”.

Case Study: Sponsorship

My first time sponsoring an item for UBC Solar was the Vicor V110A12C300BL DCDC converter. Hearing that the team had previously been sponsored by Vicor, I sent the company an email, and a few weeks later, had a tracking number for the free component in my inbox. This sparked my realization that if I was able to proactively anticipate items the team would need for development and manufacturing, a couple hours of my time could save the team thousands of dollars.

The key word here is proactive. The lead time for most sponsors ranges from three weeks to three months, and as such, the only way I could successfully sponsor an item for the team was if I incorporated it into project timelines. My push for sponsorship across both the mechanical and electrical teams encouraged members to actively anticipate the team’s needs and visualize what a project’s final, successful form would look like.

Each time I’d think of an item the team would need, I’d spend about an hour and a half emailing 5-10 companies who might be willing to donate the item to us. If I was lucky, one or two companies might respond positively or negatively. More often than not, I wouldn’t receive a response in the first place. However, if a company was local, or very specialized, I’d call them or find other departments within their company to email. In the majority of these instances, I’d receive a positive response, which fueled my energy to push for more sponsorships in the future.

Sponsorship Hunting

The longest a sponsorship ever took was 6 months. I initially emailed a company to request sponsorship of our radio modules, and while they responded to my request with interest, subsequent follow-ups from me yielded no further emails. Undeterred, I contacted the representative on LinkedIn, and, hearing no response, asked Serhii to do the same. After a few weeks, the rep responded to Serhii and agreed to send out parts to the team, however, they sent them to the wrong address (in Boston). After a month, we received the parts, only to realize they were the less powerful version of the part we requested. A month later, we finally received the correct parts, just in time for integration onto the car.

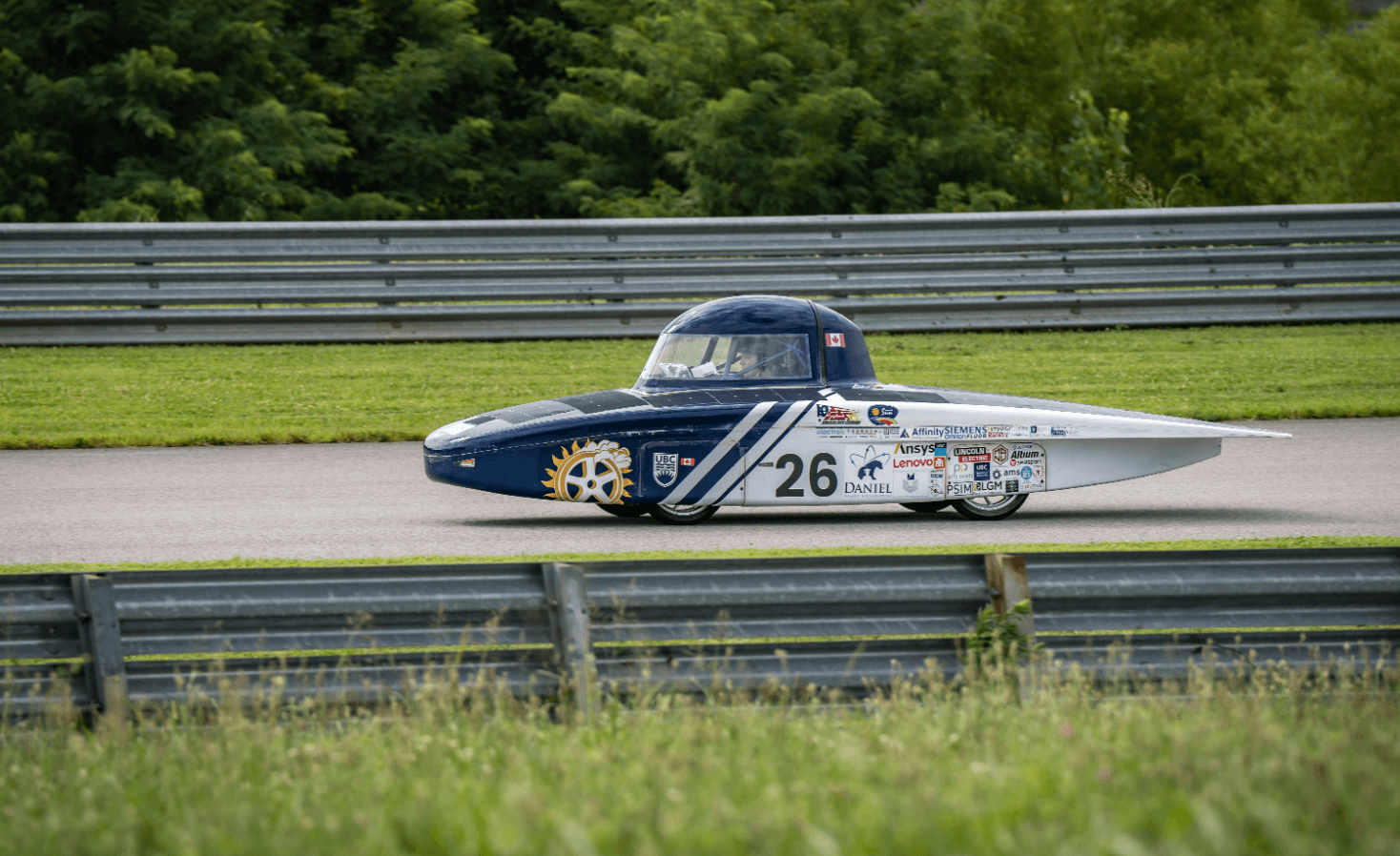

UBC Solar’s sponsors displayed on the side of the car at FSGP 2024

The sponsor I was most proud of connecting to the team was ECS. ECS is a local wire supplier located in Richmond, who was very receptive to my requests for sponsorship. Not only did they agree to donate hundreds of meters of wire for our low-voltage systems and our high voltage arrays, they actively wanted to collaborate on media and press to promote the sponsorship. Increasing the team’s public presence was another factor that fed into my mindset of running UBC Solar like a startup - I remember taking a meeting with ECS in one of Sanctuary AI’s meeting rooms, while across the way in the conference room, the C-suite of the company was meeting with potential investors.

Some additional examples of ideas that’ve sparked my curiosity, or I’ve thought of and implemented, are detailed below.

NCAN

Below is a picture of a PCAN CAN bus analyzer which goes for ~$500CAD retail.

Early on, I knew that having multiple CAN-USB devices available to the team would be essential for debugging any piece of firmware or hardware on the car. In case I wasn’t able to get these devices sponsored, Nic and I brainstormed an alternative solution - the NCAN. This was a $15CAD fully-assembled board that was meant to act as a drop-in alternative to the PCAN. In the interest of “getting an MVP that works”, over two months, the team developed a PCB based off open-source designs that could be flashed with open-source firmware.

While the device wasn’t exactly a drop-in replacement (didn’t work with PCAN-View all the time), we’d proved out a scalable in-house CAN-USB analyzer that worked with 90% of open-source Windows and Linux CAN analysis software.

Elec Space Organization

If you couldn’t already tell, I like organizing things. After organizing the electrical team’s project management Monday space, I turned to making the physical electrical space work better for the team. While, at the end of the winter break in January 2023, Serhii, Liam F, and I had renovated the entire bay, the electrical team’s boxes were still disorganized, and sometimes it was easier to just purchase a new component than it was to find it.

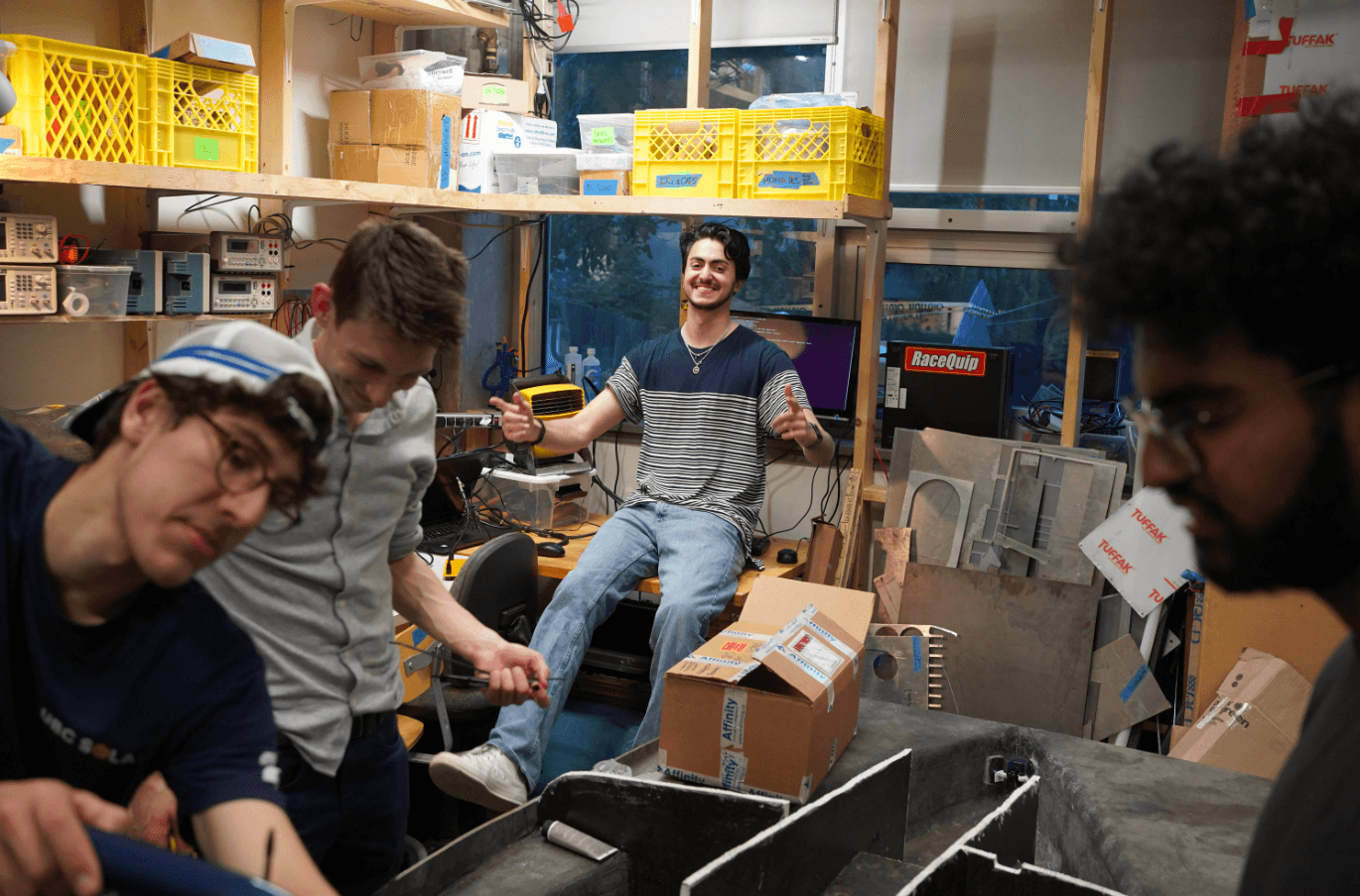

Renovating UBC Solar’s bay, an ownership-enforcing rite-of-passage for new exec teams

During the summer of 2023, I put up a new shelf in the electrical space to hold oscilloscopes and function generators, created dedicated boxes for firmware and hardware prototyping, and went on a labelling spree for all of elec’s boxes (with the Electrical Inventory being the last part of this process). I also put up lightning and spare monitors that made the space more usable and enticing to work in.

As a non-obvious example, while working on the battery one day, I noticed that at some point, all the stacked-up cardboard boxes above the workbench could easily get jostled and fall into the pack. I thought for a second, then grabbed a milkcrate sitting outside and stuffed three of the cardboard boxes inside of it. Just like that, I’d removed a hazard from the space. After this, I kept two spare milk crates around the bay at all times. Incidentally, the first person to inspire this milk-crate-craze? Joe.

Elec Computer

In order to persist telemetry data and enable quick benchtop monitoring of the battery, I grabbed an old HP tower I had lying around the house, installed Ubuntu Desktop on it, and set it up in the bay. A simple, hour-long process that unlocked numerous debugging and data-collection options for the team.

Visiting Other Teams

After competition in mid-August, I flew to Montreal for a vacation with some friends. The week before I left, I reached out to Eclipse at ETS and Esteban at Polytechnique Montreal to see if they’d be willing to give me a tour of their workspaces. They generously agreed, and I was fortunate enough to spend around four hours with each team, asking questions about everything from battery pack design to financial structure.

Esteban’s workspace tour, graciously hosted by their Electrical Lead (pictured) and Captain

Eclipse’s workspace tour, graciously hosted by their Mech Lead (pictured) and members

This visit was very special to me, as ETS was the winner of FSGP 2024, and one of the top 10 teams on the world solar racing stage in the SOV category. Esteban holds similar credentials in the MOV category - a repeat winner of FSGP and ASC, and a top competitor in the World Solar Challenge. Going from watching ETS in the Lightspeed documentary on my first day of UBC Solar to meeting them as Electrical Lead of the 6th place team at FSGP 2024 was a profound experience.

In addition, I wanted to make this visit a big deal for the new generation of UBC Solar. When I returned to Vancouver, I presented on my visit to the team to show them that UBC Solar had grown to become a real competitor on the level of some of the top teams in North America. I evoked a sense of pride in UBC Solar’s accomplishments, and showed the team that if we pushed ourselves, we could end up at the same level as these top teams. I also wanted to spark the same curiosity and excitement towards new ideas and design team innovation that I felt by showing the team, “hey, this is how this other students accomplish the same objectives we’re working towards”, opening the team’s collective consciousness to questioning assumptions of our own high level abilities.

Finally, these visits built invaluable inter-team connections that set the foundation for the knowledge sharing that is currently happening between our teams on everything from power electronics to material testing.

Bay Camera

My objective? To get the team to take more professional photos and videos in the interest of generating sponsorship content. I transferred my old Linux GH4 from the shelf in my room where it was gathering dust to a space in the bay where anyone on the team could access it. The chassis was being welded? Get some footage. The aeroshell folks were working on a layup? Take some photos for the composite materials sponsor.

After a year, having this camera present netted the team invaluable, professional-looking media that could be used for everything from recruitment to sponsorship.

Battery Safety

UBC Solar’s battery team has always been safe in designing and working with their battery packs, and coming from a background of lifeguarding, I took this culture of safety very seriously. I created the first team presentation on battery safety and created the first SOP formalizing the team’s rules around working with the battery pack. Once the pack was assembled, I was constantly looking to improve its safety, such as asking BTM to print out 3D printed covers for busbars and contactors. Finally, I learned from Joe about Formula E’s battery precautions and how to avoid the types of accidents they, and other teams, had experienced in the past. Overall, I’m proud to say that there were zero battery incidents during my time as BMS and Electrical Lead.

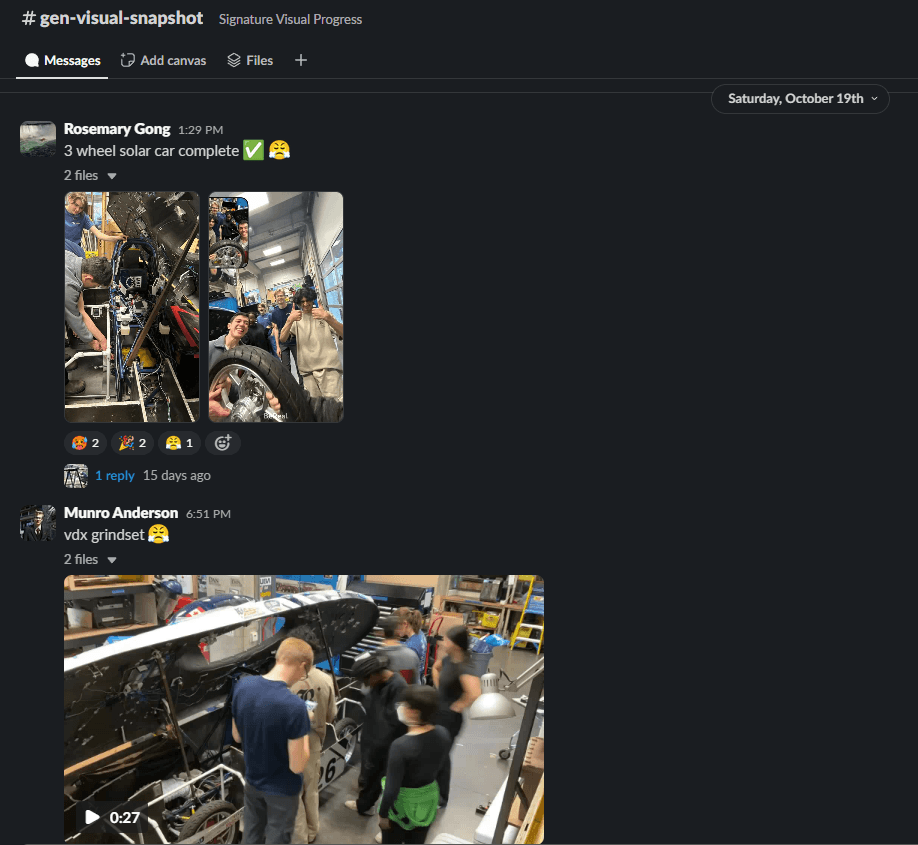

gen-visual-snapshot

This was a channel that Serhii and I created in Slack inspired by a similar channel at Sanctuary AI. This channel was meant for organization-wide pictures and videos related to cool achievements and progress reports. This low-effort, high-value change gave folks a look into what other subteams were working on while showcasing other member’s dedication. Posting a picture in gen-vis evoked a sense of pride and ownership over one’s work and generally increased the team’s motivation and cohesive spirit.

VDX’s progress shared with the team in the gen-visual-snapshot channel

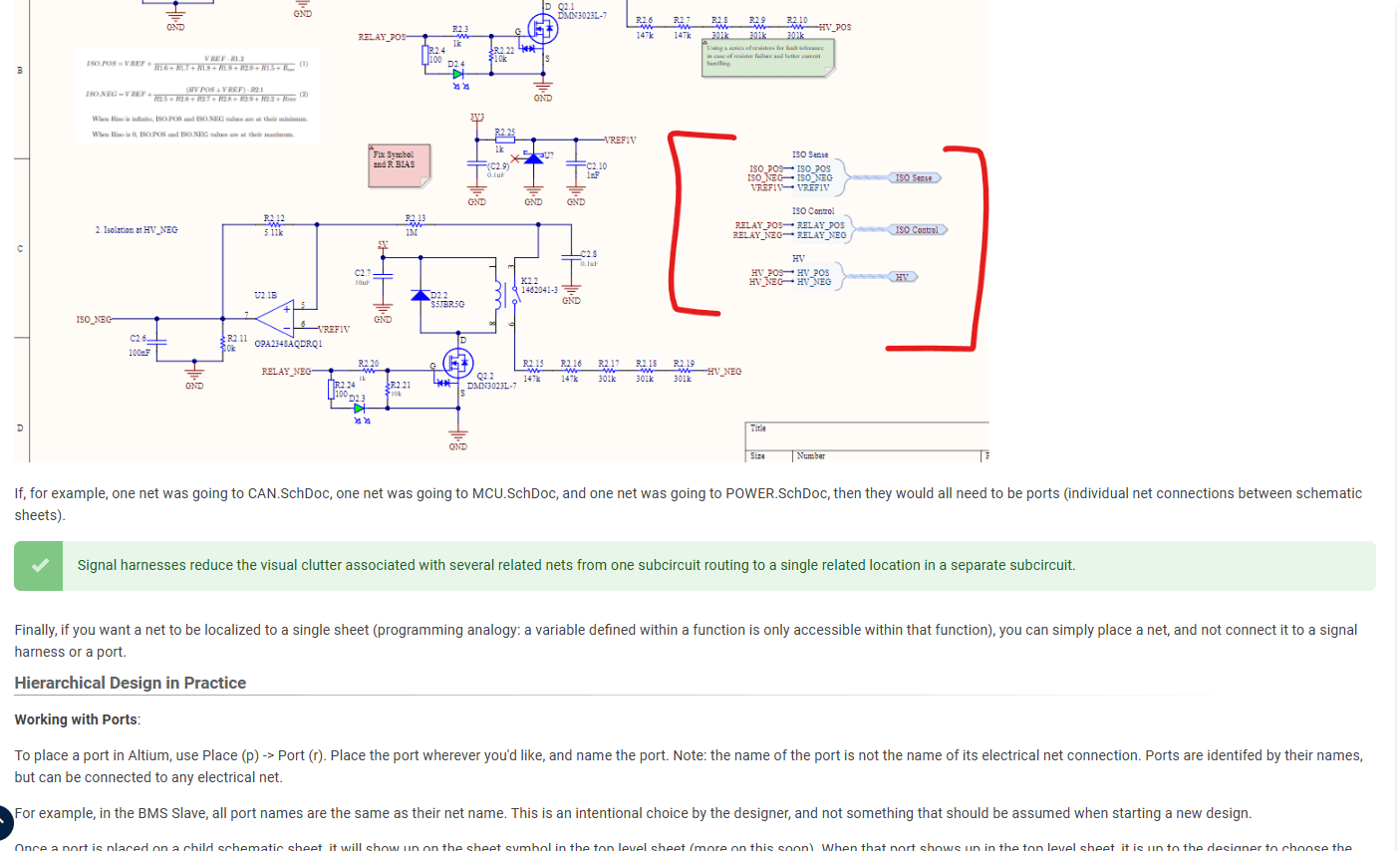

Hierarchical Schematic Design

With the completion of the NCAN, Nic had provided the team a project implementing industry-standard Altium best practices. I codified the intention (Vocalize the Why) and rules followed in his design into a standard for UBC Solar’s hierarchical design, while trialing this standard on two projects being undertaken by members new to working with Altium. During this process, I encouraged them to contribute their learning and recommendations to the wiki page to build out the team’s documentation and make the standard more designer-friendly.

An excerpt from the section in the Altium tutorial wiki page on hierarchical design

This will be a huge step-up for the team in terms of professionalism, organization, and decreasing schematic loading times in Altium 365.

Passionate Members

While it was initially difficult to take over as Electrical Lead due to the team lacking focus and drive, every member was passionate about the project and motivated to contribute. As the frameworks that the Captain, Mech Lead, and I visioned began to be implemented and ingrained into the team’s spirit, the feeling of being a lead transitioned from pushing the team forward to being pushed forward by the team.

At the beginning of this post, I said that UBC Solar was the most important part of my life over the past four years because of the community I became connected to and subsequently strove to connect others to. Every single action I took as lead was to strengthen a world-class team that designs, builds, and races solar powered cars, and the only reason I could push myself so hard towards this objective was because there was a driven team working just as hard around me. Essentially, I’d helped build a team that would hold me accountable.

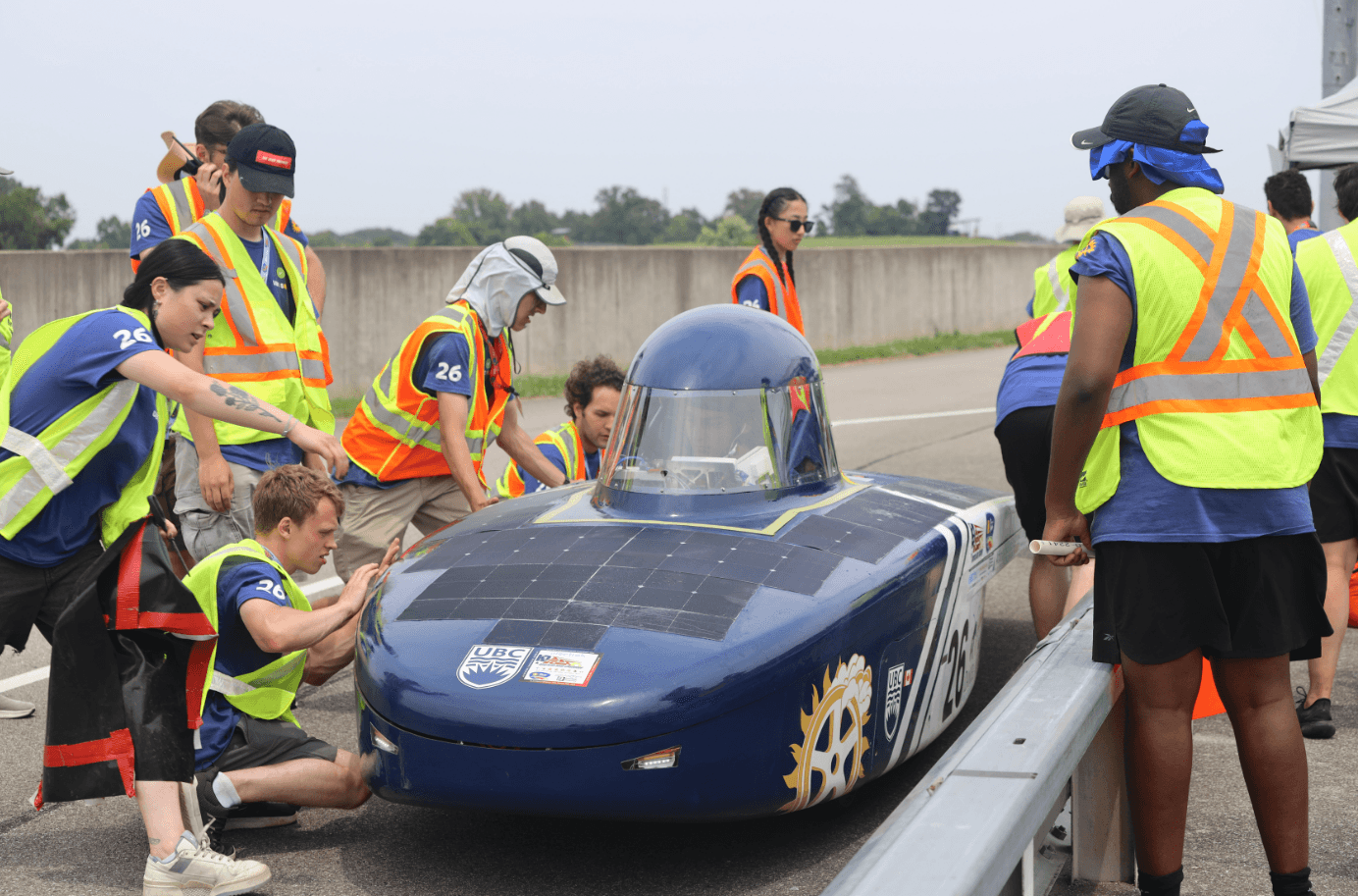

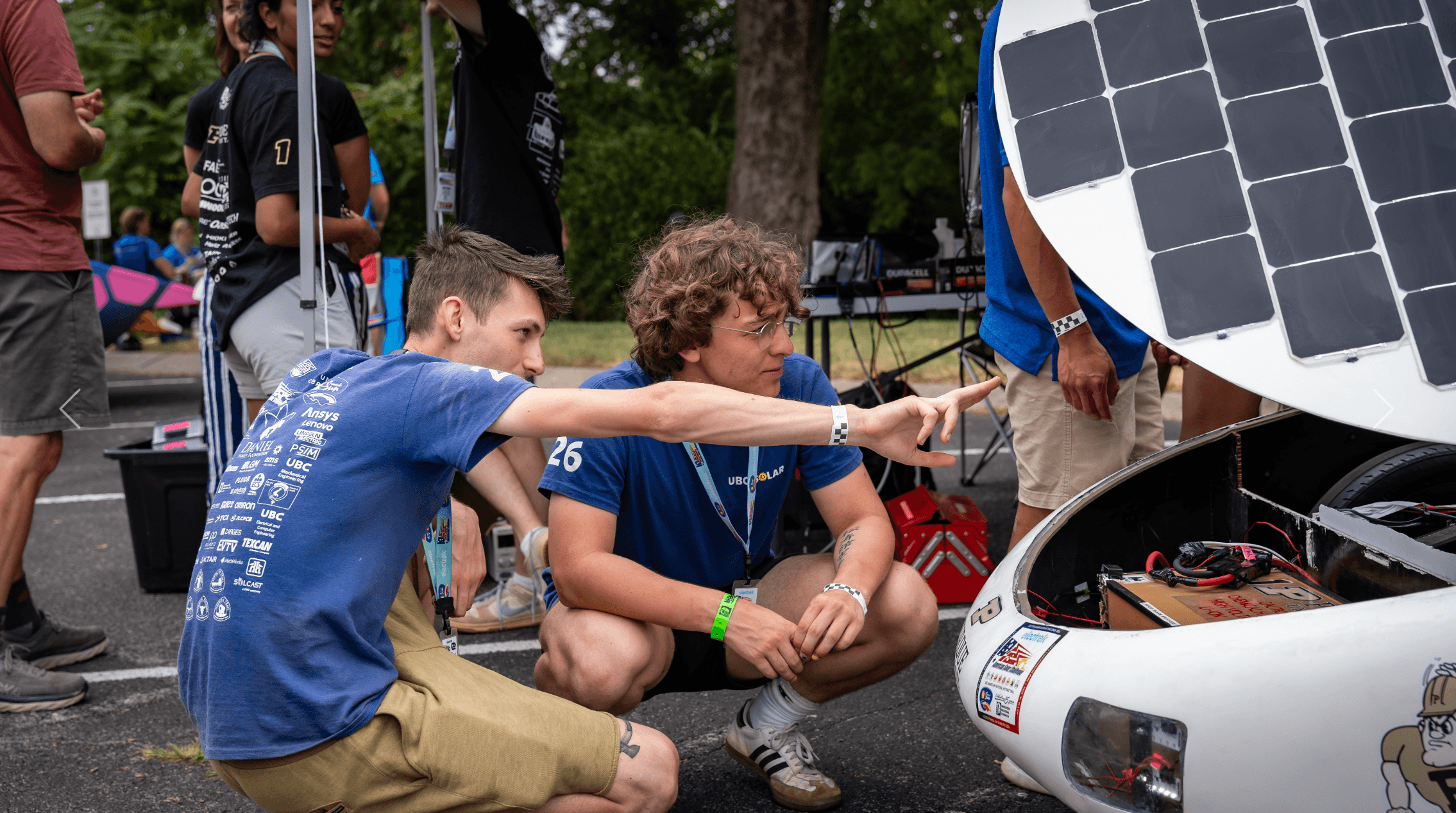

The team executing a pit stop on the first day of FSGP

I clearly remember the first time I felt like I’d succeeded in building a distributed, motivated team - in January 2023 helped Tigran, Sam, and Krish set up a test to validate the ADC firmware on the ECU. After checking over their procedure, I let them know they were good to go, and headed out for the night. On the way to the bus stop, I couldn’t help but grin at the fact that I was able to trust my team to work without my oversight, a goal I’d been driving towards for almost a year at that point.

As we approached competition, the momentum and independence of the members that dedicated their summer to finishing the car astounded me, and it was at that point that I truly understood what it meant to be a part of a design team. I no longer needed to message people to check in on their progress, or hold 1-1s with leads to see whether milestones were met. These folks, working hard whether it was 6AM or or 2AM, would come to me with updates, or better yet, tell me that I was blocking their progress.

Throughout my time as Electrical Lead, there were many members who impressed me with their technical skills and motivation, however, I want to highlight three members who grew to make the experience of being on the team at UBC Solar extraordinarily rewarding and exciting with their own drive and curiosity.

Ben

Ben had been on the team for as long as I had, and had become lead of the newly-formed PAS team just after I became Electrical Lead. Over time, Ben quickly became the best PAS lead that an Electrical Lead could ask for due to his intense attention to detail, a deep understanding of the power electronics theory behind our technical challenges, and his ownership over the team’s success.

After Ben became lead, I remember introducing the DR0 document to him for the first time, and I could tell he was skeptical of its usefulness. It was this skepticism and no-bullshit attitude that I came to truly appreciate, and later rely on, leading up to competition. Working with Ben, I was forced to thoroughly explain my engineering reasoning and convince him of the value of technical and project management decisions - if I couldn’t convince him of something, chances are it wasn’t useful in the first place. I will never forget Ben and I going over the car’s high voltage wire gauge sizing before electrical scrutineering, and after we’d written it all out, him saying “ok, now explain it all back to me”. Ben and I are both engineers who won’t accept less than 100% effort and completeness, and we held each other to this during tough times of no sleep and tight timelines (and always with a grin on his face).

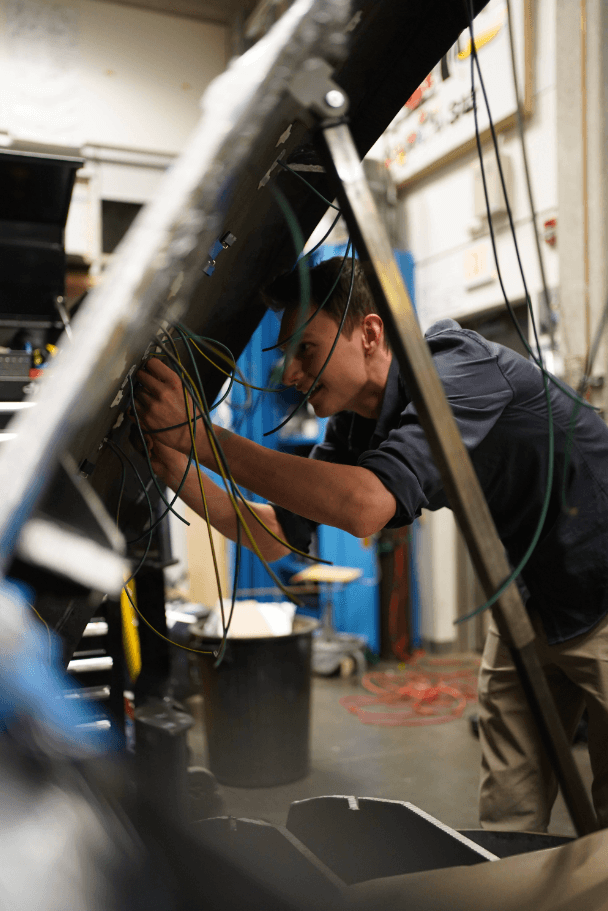

Ben working on wiring up Brightside’s array

At the same time, I came to rely on Ben’s deep power electronics expertise combined with his sharp attention to detail, which elevated the entire team’s standards and technical abilities. From complex projects like cruise control to array energy modelling, Ben and I worked well as a team, as he wrapped his engineering first-principals knowledge around the executive team’s scaffolding of project management frameworks. This allowed us to achieve technical milestones I wouldn’t have considered possible (or even imagined in the first place) prior to Ben growing into increasing responsibility as lead.

Finally, I was so proud of Ben’s growth as a mentor and teacher. When he stepped up as PAS lead, I could tell that he’d put himself into a role that he wasn’t instantly comfortable with. However, his persistence to learn and willingness to integrate new ideas while staying true to his own technical frameworks lead to immense growth and success as a project manager and engineer. An example of this was the array wiring diagram that Ben put together with PAS members Saman and Michelle. Ben leveraged his experience with high voltage wiring and power distribution systems to lead Saman and Michelle to make informed choices on wire size, length, and routing configurations. He independently encouraged his members to set up meetings with the aeroshell team to work on the location of array wire cutouts, and helped Saman put together a detailed plan for the array testing, soldering, and wiring process. The team is forever in Ben’s debt for forcing me to give more time to the array wiring and testing integration deadlines. Ben knew that it would take 5-7 days to fully wire up and test the arrays, longer than the 1-2 days I’d considered. Since I wasn’t able to convince Ben otherwise, I trusted his analysis of the situation, and put more focus and energy into integrating the arrays into the car, a decision which paid off considerably to decrease stress and increase the reliability and power generated by our arrays at competition.

Presently, it’s so heartening to see Ben participating in the team as an active alumni, initiating discussions with Race Strategy members on data analysis while providing advice to Saman on the roadmap to building own our custom MPPTs. This, from a Ben who, two years ago, wasn’t sure whether he wanted to be a lead in the first place.

Ben making an observation to Diego about Purdue’s array configuration

Saman

Saman is the definition of a member whose attention to detail lead him to success on the team. The first time I sat down to discuss a project’s progress with Saman, he pulled out his iPad, and showed me the detailed notes he’d made and the questions he’d prepared. I immediately recognized someone who worked in a similar way to how I’d worked as a BMS member, and as lead, I felt determined to set Saman up for success in the ways I was, and wished I was, as a member.

Every challenge I presented to Saman, he tackled with energy and hard work. For example, after revisiting the requirements of our telemetry system, we realized we needed to conduct detailed range tests on our current radio modules to ensure they could meet our new transmission distance requirements. I encouraged Saman to lead this project from the PAS side, and set him up with my expectations of how the test should be planned and documented. Within this framework, Saman was able to flex his project management muscles for the first time, coordinating with EMBD members to execute, document, and present the results of the test to the team. Throughout the process, Saman consistently communicated his results with the leadership team and incorporated my feedback into his work.

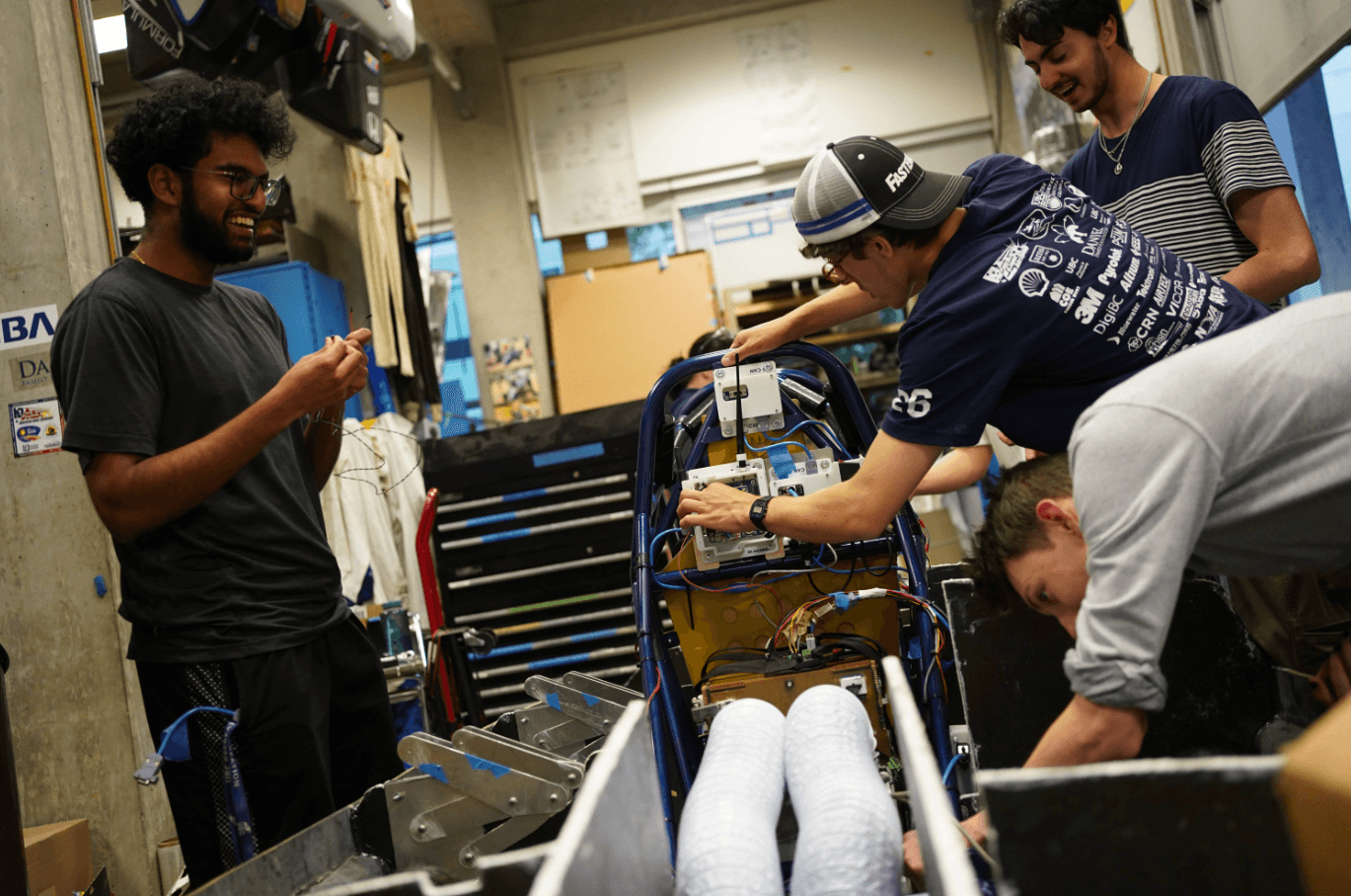

Saman making Ben, Aarjav, and I laugh while installing the car’s wiring

The reason Saman excelled at documentation was that he was a very curious individual. Similar to me, he needed to understand the fundamental principals behind the devices he was working with at every level of abstraction. Often, Saman would ask me questions that made me say, “that’s a great question - I don’t know the answer, but let’s find out together”. This hunger for technical understanding was what made Ben and Saman such a successful member-lead pairing. While working on the array energy modelling project, he ran with fairly open-ended requirements, and each time we met, he would excitedly present new findings and project objectives he’d developed from his research.

Over time, Saman lead up more and more on critical projects and in the process, taught me important information about the systems we were working with through his extensive Monday updates. On the same radio systems project mentioned above, Saman was the first member on the team (that I was aware of) who read the module’s datasheet cover-to-cover, and because of this, was able to bring up important features of the device that were previously unknown to the team.

Currently, Saman is doing an exceptional job as the team’s Electrical Lead. He has brought his focus and insatiable curiosity to improving the Race Strategy team’s algorithms, data analysis workflows, and modelling of the car, and has channeled his upbeat energy into increasing the momentum of the electrical team, bringing in new frameworks related to prototyping and increasing the reliability of the team’s design process.

Aarjav

Aarjav, currently the embedded co-lead, is one of the smartest-working people I know. Aarjav is not only able to understand and visualize complex systems and open-ended projects, he’s able to produce results in half the time I’d expect, with double the quality of work, and triple the level of documentation.

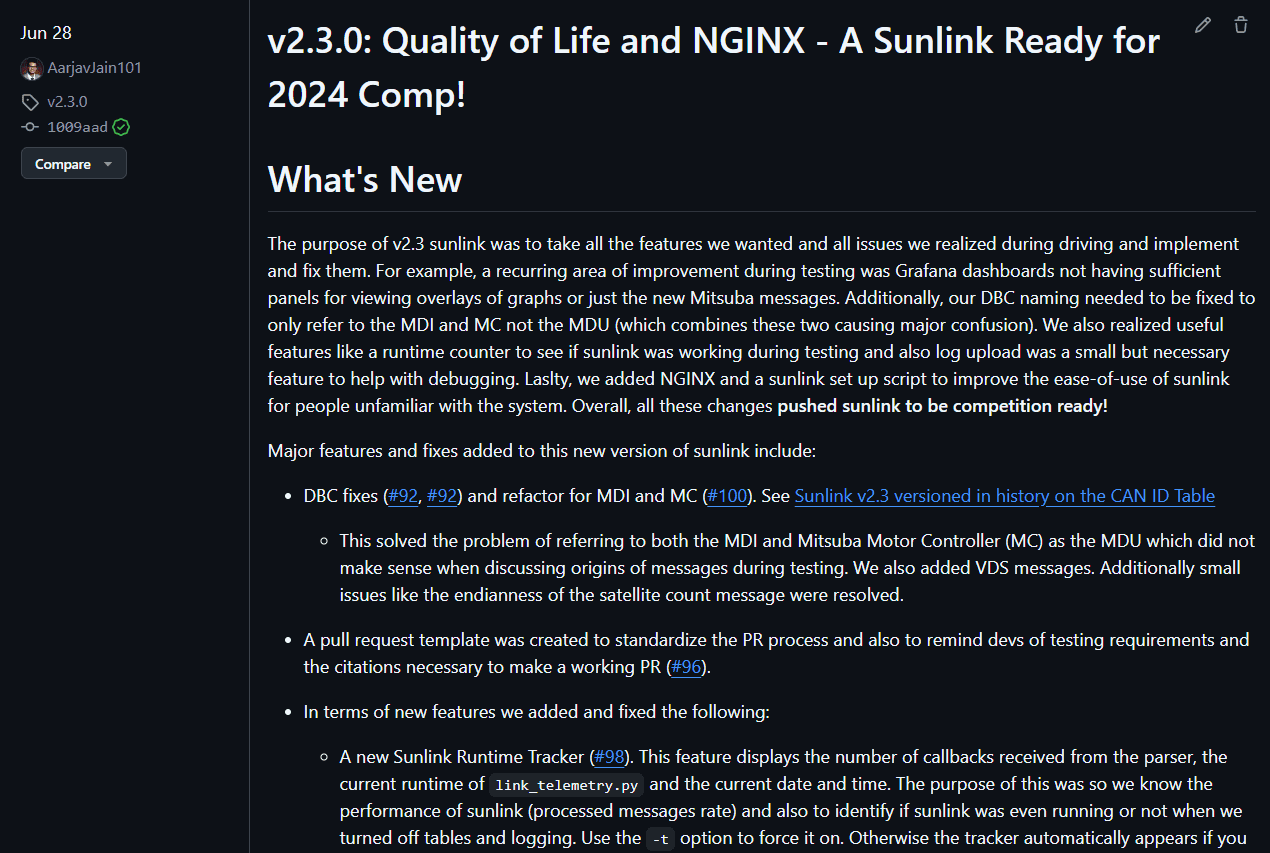

As a lead, it’s important to recognize that setting members up for success looks different for each individual. Setting Aarjav up for success looked like giving him a clear vision and purpose for a complex technical project, and then staying on top of his progress to course-correct as he chewed through code and documentation. Aarjav began making strides on the team when he started refactoring Sunlink, the data processing, storage, and visualization software stack of UBC Solar’s telemetry system. As the changes he made to the project quickly surpassed the project’s MVP, I channeled Aarjav’s attention toward documenting his changes on Monday and in Sunlink releases.

Clear Communication

Aarjav, more than any member on the team, focused on his vocabulary and phrasing when discussing technical concepts. Aarjav habitually grounded his conversations in concrete technical language, rephrasing and reiterating to ensure everyone participating in the discussion was on the same page as he introduced new concepts.

I quickly realized that Aarjav embraced documentation even more than I did - he wrote several READMEs on the new software architecture he’d created the previous week, made detailed Monday updates that I highlighted to the team as examples that I personally wanted to mimic, and generally elevated the embedded team’s standards for what detailed, professional documentation and code structure looked like. Aarjav pushed the team’s pace forward, holding Ishan and I accountable to keep just ahead of his progress.

Aarjav leading the Telemetry system’s bringup and debugging

Aarjav’s intentional, detailed documentation lead the telemetry system - the most important and complicated electrical system on the car - to a roaring success as he lead its bringup, integration, and debugging in the month prior to competition. There were many nights when I’d leave the bay at 11PM and Aarjav would be in the atrium continuing to debug the latest issue with the telemetry system, only pausing to wave a friendly, energetic goodbye. Aarjav owned his projects from beginning to end - I never felt the need to nag him about timelines or requirements, because I knew he’d internalized these aspects at the project’s inception.

A detailed release note written by Aarjav for Sunlink

I was pleasantly surprised to find that the team relied on Aarjav more and more as we closed in on competition. The first day we drove after the topshell was installed on the car, the Memorator wasn’t sending its timestamp messages over CAN. Aarjav, back home in Calgary at the time, was instantly available to hop on call and point me to the detailed documentation he’d written as to how to reconfigure and flash the Memorator, a device he’d only been introduced to a couple weeks before. It was a testament to Aarjav’s detailed, hard work that Sunlink and the rest of the telemetry system worked 100% of the time at competition, preserving invaluable data that will allow the team to level-up its future designs and strategy.

Aarjav’s independent and accelerated work ethic, along with his huge curiosity, lead him to learn and contribute to almost every single piece of firmware on the car. If we were having trouble with the MDI firmware, Aarjav would be able to parse and suggest changes to it within the hour, while asking thought-provoking questions about the high-level design intent of the project. At present, I’ll see Aarjav contributing to discussions in Slack threads from every single electrical subteam, pushing his fellow members and leads to work faster and more intentionally.

In Closing

While my time on the team started as a way to boost my resume and technical skills, it grew into a life-changing experience that pushed me far beyond the limits of what I’d ever imagined I could accomplish, and gave me the privilege of learning from and working with a community of some of the most driven, passionate, and energetic engineers to build a freaking solar powered race car.

I do not feel as though I’m finished with UBC Solar. As with any community that’s impacted you positively, I believe it’s important to continue to contribute to the community’s spirit. I will never part with the experiences I had at UBC Solar, and I know I will forever be a member of the most amazing design team in the world.

UBC S

LAR

manager@ubcsolar.com

©2025 UBC Solar. All rights reserved.